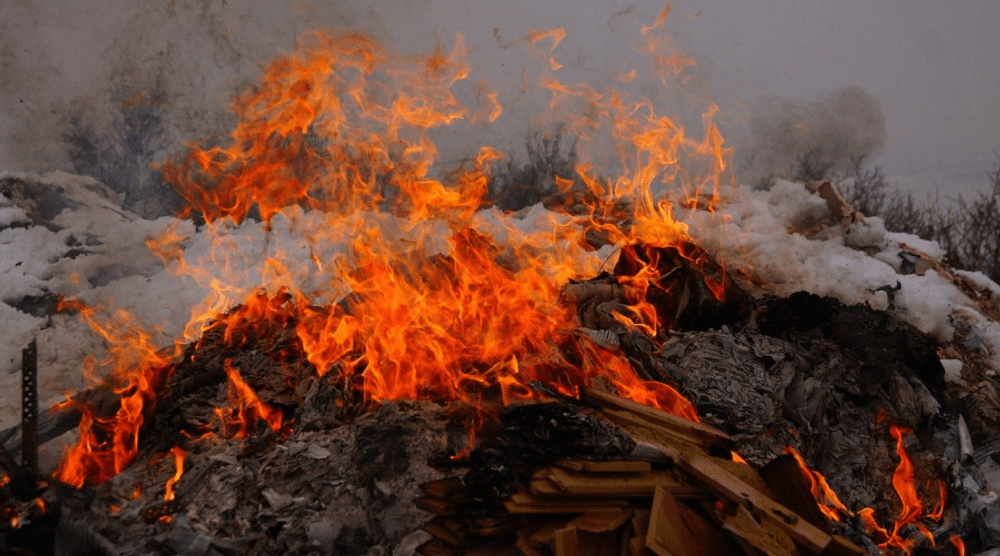

Zombie fires arise as a consequence of wildfires. They've named zombie fires as they appear to appear back from the dead. After a wildfire has been suppressed on the surface, some of it can regardless burn below the ground hidden, mostly fuelled by peat and methane.

These fires can continue to burn all through winters, surrounded under a covering of snow, and in spring when the temperature rises, the snow melts, and the ground dries out, the wildfires can re-ignite and scatter once again.

Zombie Fires

The fire season in the Arctic has been kicking unusually early, last year as early as May, there were flames flashing north of the tree line in Siberia, which generally wouldn't come up until through July.

One justification is that temperatures in winter and spring were warmer than normal, preparing the landscape to burn. It's furthermore apparent that peat flames had stood smoldering beneath the snow all winter and then rose up, zombie-like, in the spring as the snow withered.

Scientists have indicated that this type of low-temperature, flameless explosion can burn in peat and different organic substances, such as coal, for months or even years.

Arctic Fire and Changes

Like all jungles, the tree-covered spans of the Arctic sometimes catch on fire. However, unlike multiple woodlands in the mid-latitudes, which grow on or even need fire to protect their health, Arctic forests have developed to burn merely infrequently.

Zombie fires are devastating portions of the Arctic, with regions of Siberia, Greenland, Alaska, and Canada consumed in fires and smoke. Zombie fires aren't completely fresh happening in the Arctic.

However, their happenings are closely associated with climate change, happening more often after hot, long summers with lots of fire and suggesting that these still-rare events could become more frequent.

Climate change is reshaping that discipline. In the first decade of the new millennium, flames burned 50 percent extra lot each year in the Arctic, on average, than any decade in the 1900s.

Between 2010 and 2020, burned lot remained to creep up, specifically in Alaska, which had its second disastrous fire year ever in 2015 and another terrible one in 2019.

Scientists have discovered that fire frequency today is higher than at any period since the appearance of boreal jungles around 3,000 years ago and potentially higher than at any case in the prior 10,000 years.

Fires in boreal woodlands can discharge even more carbon than the same fires in locations like California or Europe because the soils underlying the high-latitude woodlands are frequently made of aged, carbon-rich peat.

Slumbering in Peat

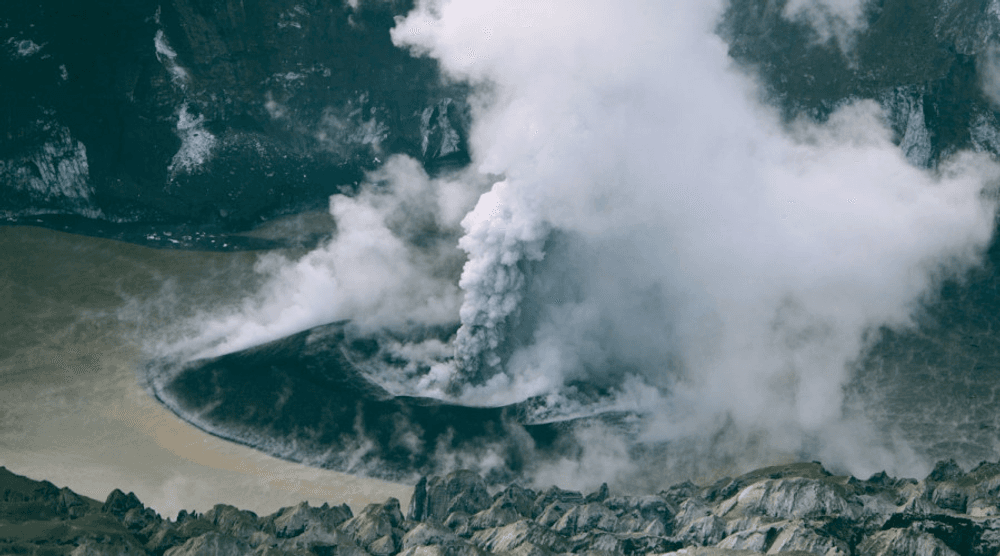

Peat is formed of lifeless vegetation, mosses remain of trees and shrubs, different Arctic plants, that hasn't been wiped out all the way. It shapes in damp and cold portions of the world, where organic material degrades gradually.

Today, peatlands cover some 4 million acres of the Arctic and reserve an assessed 415 billion tons of carbon, many times extra than the woodlands above them and as much as all the trees on the Planet.

Elsewhere on the planet, soils don't usually encompass much burnable organic substance, so flames feed on what they come across like trees, shrubs, homes, at the ground.

In the Arctic, fires usually begin at the ground too, provoked by summer lightning or sometimes by humans.

However under the sorts of climate-changed circumstances becoming extra common there that are extra extended, heated summers with extremely pressing heat waves that suck the moisture out of plants and soils, the moist underlying peat can burn.

The Long Burn

The presence of zombie fires called "overwintering" or "holdover" fires by most experts has been recognized for a while. In 1941, for example, a human-caused fire along an Alaskan railway line burned approximately 400,000 acres.

The next May it burst up again; by the time it was ultimately extinguished it had consumed approximately another 300,000 acres.

In more current decades, administrators in Alaska and the Northwest Regions have kept trace of dozens of overwintering flames their staffs have confronted.

However, scientists hadn't formally recognized whether there were further zombie fires burning away unlisted, or whether they were getting more continual as the Arctic climate quickly warmed though they believed that was possible.

An Arctic Furnace Warming the Planet

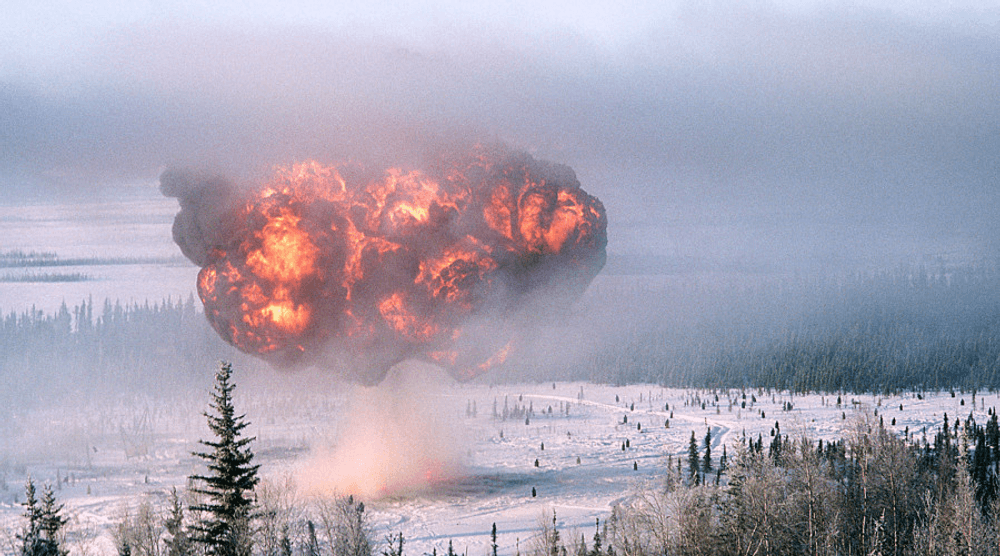

As Arctic fires evolve less unusual, they linger unusual among different flames because their consequence spreads thousands of miles beyond their physical radius. One far-reaching consequence of these fires is slime.

As the fires enter elevated into the sky, they pour particles generated of black carbon, one of the primary components in soot in every direction.

These components are like what might plunge out of a chimney, but they furthermore wander unobserved in the polluted atmosphere and can be toxic to living creatures, intensifying the possibilities of asthma attacks, strokes, heart attacks, and different potentially deadly chronic health conditions.

And black carbon doesn't only impact on humans, it furthermore impacts on the health of the Arctic as a whole. Snow and ice are extremely significant to the Arctic because they enable it to keep up cool by reflecting sunlight off its white surfaces back into the atmosphere this is one of the justifications why recent ice melts in the Arctic have created the area even warmer.

However, when there is soot in the atmosphere, it ultimately nestles down in coatings on the white Arctic terrain and turns it black. Then these unusual black grounds can consume heat and trap it at ground level, which enhances the Arctic warming cycle.

However, where there's smoke, there isn't always fire at least not at the ground. When peat burns, it doesn't flame up like ordinary fires; rather, because it is belowground, it smolders beneath the ground.

These so-called "zombie fires" are nonetheless identifiable by the wisps of smoke surging from the ground, but because they burn sluggisher and extra subtly and can't be easily extinguished, they can turn out burning for considerably longer even through the winter and eventually discharge many extra emissions into the air.

These emissions encompass black carbon particles, but furthermore carbon-containing gases, which we generally understand of in the classification of greenhouse gases.

These gases hover in our air, where they soak and radiate heat to keep the Earth warm, like a greenhouse encircling our earth. However, when too much reach the atmosphere like when we burn fossil fuels these gases do their task too adequately and render the planet warmer than it should be.

Arctic fires discharge carbon-containing gases like carbon monoxide and methane, exactly like cars burning gasoline. Still, because the chemical composition of the soil is further different than fossil fuels, it moreover generates greenhouse gases like nitrous oxide that don't comprise carbon but nonetheless trap heat.

Because the Arctic contains such heavy reserves of carbon, fires that burn through it open the floodgates and discharge enormous quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

One peat fire can generate 80 tons of carbon per acre, equal to the yearly emissions of approximately 20 cars. Multiply this by the millions of acres of fires forming each summer, and the quantity skyrockets.

What Can be Done to Resolve the Issue?

According to the latest research, there is a serious demand to understand the essence of fires in the Arctic that are growing and transforming quickly. The research asserts that the problem is so significant to the climate system that it had to be embraced as an issue of worldwide significance.

The research has urged global alliance, investment, and action in monitoring fires and called for understanding from the indigenous communities of the Arctic about how the fire was traditionally borrowed. The research furthermore recommended that fresh permafrost and peat-sensitive approaches to wildland fire fighting were required to protect the Arctic.